I've published an activator template of how to integrate JMX into your Akka Actors. Using this method, you can look inside a running Akka application and see exactly what sort of state your actors are in. Thanks to Jamie Allen for the idea in his book, Effective Akka.

Running

Start up Activator with the following options:

export JAVA_OPTS="-XX:+UnlockCommercialFeatures -XX:+FlightRecorder -XX:FlightRecorderOptions=samplethreads=true -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.port=9191 -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.authenticate=false -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.ssl=false -Djava.rmi.server.hostname=localhost"

export java_opts=$JAVA_OPTS

activator "runMain jmxexample.Main"

Then in another console, start up your JMX tool. In this example, we are using :

jmc

- Using Java Mission Control, connect to the NettyServer application listed in the right tree view.

- Go to "MBean Server" item in the tree view on the right.

- Click on "MBean Browser" in the second tab at the bottom.

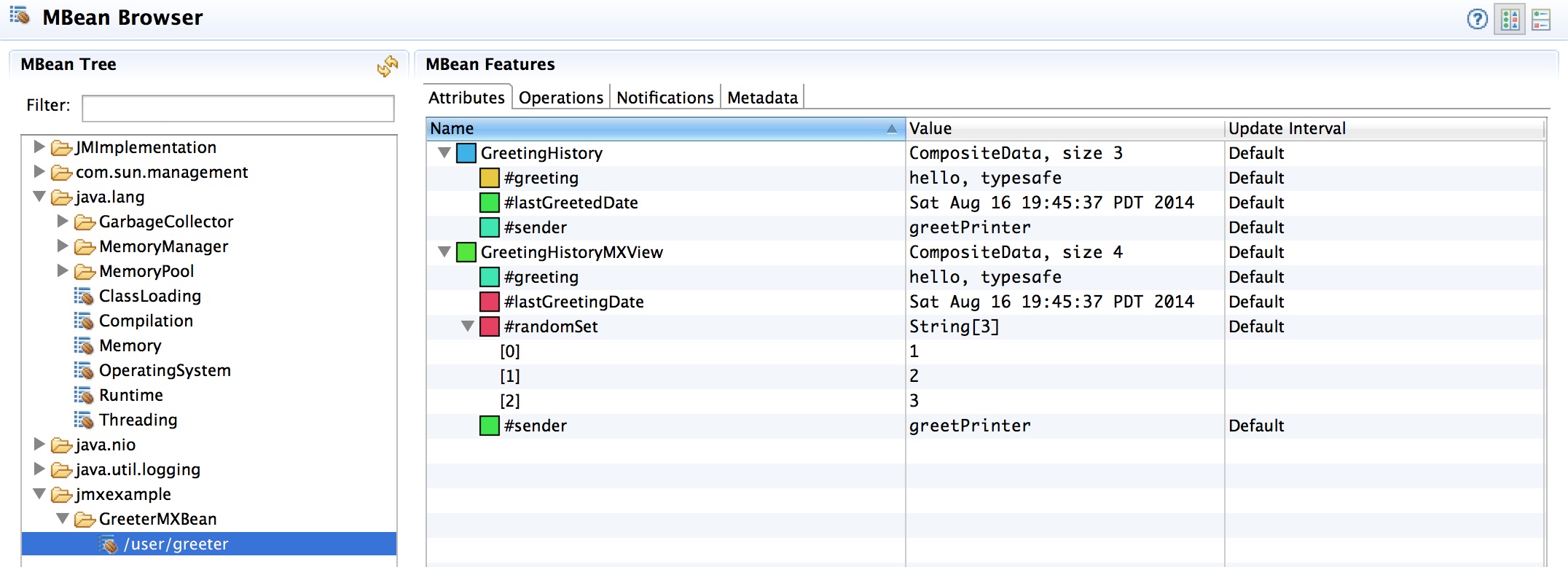

- Open up the "jmxexample" tree folder, then "GreeterMXBean", then "/user/master". You'll see the attributes on the right.

- Hit F5 a lot to refresh.

You should see this:

##Creating an MXBean with an External View Class

Exposing state through JMX is easy, as long as you play by the rules: always use an MXBean (which does not require JAR downloads over RMI), always think about thread safety when exposing internal variables, and always create a custom class that provides a view that the MXBean is happy with.

Here's a trait that exposes some state, GreetingHistory. As long as the trait ends in "MXBean", JMX is happy. It will display the properties defined in that trait.

/**

* MXBean interface: this determines what the JMX tool will see.

*/

trait GreeterMXBean {

/**

* Uses composite data view to show the greeting history.

*/

def getGreetingHistory: GreetingHistory

/**

* Uses a mapping JMX to show the greeting history.

*/

def getGreetingHistoryMXView: GreetingHistoryMXView

}

Here's the JMX actor that implements the GreeterMXBean interface. Note that the only thing it does is receive a GreeterHistory case class, and then renders it. There is a catch, however: because the greetingHistory variable is accessed both through Akka and through a JMX thread, it must be declared as volatile so that memory access is atomic.

/**

* The JMX view into the Greeter

*/

class GreeterMXBeanActor extends ActorWithJMX with GreeterMXBean {

// @volatile needed because JMX and the actor model access from different threads

@volatile private[this] var greetingHistory: Option[GreetingHistory] = None

def receive = {

case gh: GreetingHistory =>

greetingHistory = Some(gh)

}

def getGreetingHistory: GreetingHistory = greetingHistory.orNull

def getGreetingHistoryMXView: GreetingHistoryMXView = greetingHistory.map(GreetingHistoryMXView(_)).orNull

// Maps the MXType to this actor.

override def getMXTypeName: String = "GreeterMXBean"

}

The actor which generates the GreetingHistory case class – the state that you want to expose – should be a parent of the JMX bean, and have a supervisor strategy that can handle JMX exceptions:

trait ActorJMXSupervisor extends Actor with ActorLogging {

import akka.actor.OneForOneStrategy

import akka.actor.SupervisorStrategy._

import scala.concurrent.duration._

override val supervisorStrategy =

OneForOneStrategy(maxNrOfRetries = 10, withinTimeRange = 1 minute) {

case e: JMRuntimeException =>

log.error(e, "Supervisor strategy STOPPING actor from errors during JMX invocation")

Stop

case e: JMException =>

log.error(e, "Supervisor strategy STOPPING actor from incorrect invocation of JMX registration")

Stop

case t =>

// Use the default supervisor strategy otherwise.

super.supervisorStrategy.decider.applyOrElse(t, (_: Any) => Escalate)

}

}

class Greeter extends Actor with ActorJMXSupervisor {

private[this] var greeting: String = ""

private[this] val jmxActor = context.actorOf(Props(classOf[GreeterMXBeanActor]), "jmx")

def receive: Receive = {

case WhoToGreet(who) =>

greeting = s"hello, $who"

case Greet =>

sender ! Greeting(greeting) // Send the current greeting back to the sender

case GreetingAcknowledged =>

// Update the JMX actor.

val greetingHistory = GreetingHistory(new java.util.Date(), greeting, sender())

jmxActor ! greetingHistory

}

}

And finally, the raw GreetingHistory case class looks like this:

case class GreetingHistory(lastGreetedDate: java.util.Date,

greeting: String,

sender: ActorRef,

randomSet:Set[String] = Set("1", "2", "3"))

This is a fairly standard Scala case class, but JMX doesn't know what to do with it. From the Open MBean Data Types chapter of the [JMX Tutorial], the only acceptable values are:

java.lang.Booleanjava.lang.Bytejava.lang.Characterjava.lang.Shortjava.lang.Integerjava.lang.Longjava.lang.Floatjava.lang.Doublejava.lang.Stringjava.math.BigIntegerjava.math.BigDecimaljavax.management.ObjectNamejavax.management.openmbean.CompositeData (interface)javax.management.openmbean.TabularData (interface)

Fortunately, it's easy to map from a case class to a view class. Here's how to display GreetingHistory using a view class for JMX, using ConstructorProperties and BeanProperties to produce a JavaBean in the format that JMX expects. Also note that Set is not visible through JMX, and JavaConverters cannot be used here to convert to java.util.Set, because it does not do a structural copy. Instead, a structural copy must be done to create a Java Set without the wrapper:

/**

* The custom MX view class for GreetingHistory. Private so it can only be

* called by the companion object.

*/

class GreetingHistoryMXView @ConstructorProperties(Array(

"lastGreetingDate",

"greeting",

"sender",

"randomSet")

) private(@BeanProperty val lastGreetingDate: java.util.Date,

@BeanProperty val greeting: String,

@BeanProperty val sender: String,

@BeanProperty val randomSet:java.util.Set[String])

/**

* Companion object for the GreetingHistory view class. Takes a GreetingHistory and

* returns GreetingHistoryMXView.

*/

object GreetingHistoryMXView {

def apply(greetingHistory: GreetingHistory): GreetingHistoryMXView = {

val lastGreetingDate: java.util.Date = greetingHistory.lastGreetedDate

val greeting: String = greetingHistory.greeting

val actorName: String = greetingHistory.sender.path.name

val randomSet = scalaToJavaSetConverter(greetingHistory.randomSet)

new GreetingHistoryMXView(lastGreetingDate, greeting, actorName, randomSet)

}

// http://stackoverflow.com/a/24840520/5266

def scalaToJavaSetConverter[T](scalaSet: Set[T]): java.util.Set[String] = {

val javaSet = new java.util.HashSet[String]()

scalaSet.foreach(entry => javaSet.add(entry.toString))

javaSet

}

}

Creating In Place JMX views with CompositeDataView

Using a view class is the recommended way to display Scala data in JMX, as it's relatively simple to set up and can be packaged outside of the main class. However, it is possible to embed the JMX logic inside the case class itself, using an in place CompositeDataView.

case class GreetingHistory(@BeanProperty lastGreetedDate: java.util.Date,

@BeanProperty greeting: String,

sender: ActorRef,

randomSet:Set[String] = Set("1", "2", "3")) extends CompositeDataView {

/**

* Converts the GreetingHistory into a CompositeData object, including the "sender" value.

*/

override def toCompositeData(ct: CompositeType): CompositeData = {

import scala.collection.JavaConverters._

// Deal with all the known properties...

val itemNames = new ListBuffer[String]()

itemNames ++= ct.keySet().asScala

val itemDescriptions = new ListBuffer[String]()

val itemTypes = new ListBuffer[OpenType[_]]()

for (item <- itemNames) {

itemDescriptions += ct.getDescription(item)

itemTypes += ct.getType(item)

}

// Add the sender here, as it doesn't correspond to a known SimpleType...

itemNames += "sender"

itemDescriptions += "the sender"

itemTypes += SimpleType.STRING

val compositeType = new CompositeType(ct.getTypeName,

ct.getDescription,

itemNames.toArray,

itemDescriptions.toArray,

itemTypes.toArray)

// Set up the data in given order explicitly.

val data = Map(

"lastGreetedDate" -> lastGreetedDate,

"greeting" -> greeting,

"sender" -> sender.path.name

).asJava

val compositeData = new CompositeDataSupport(compositeType, data)

require(ct.isValue(compositeData))

compositeData

}

}

This is messier than using a view, and does not really give you any more programmatic control. It does, however, minimize the number of types that need to be created.

Finally, the type which registers the JMX Actor with JMX is defined here:

trait ActorWithJMX extends Actor {

import jmxexample.AkkaJmxRegistrar._

val objName = new ObjectName("jmxexample", {

import scala.collection.JavaConverters._

new java.util.Hashtable(

Map(

"name" -> self.path.toStringWithoutAddress,

"type" -> getMXTypeName

).asJava

)

})

def getMXTypeName : String

override def preStart() = mbs.registerMBean(this, objName)

override def postStop() = mbs.unregisterMBean(objName)

}

The MXTypeName is defined by the implementing class, and the actor is defined with its path name and registered in the preStart method when the actor is instantiated.

Note that because this trait extends preStart and postStop, any actor implementing this trait needs to explicitly call super.preStart and super.postStop when overriding, to preserve this behavior.

Future Directions

There's a number of things that can be done with JMX, particularly if macros are involved. Actors are shown here because they are notoriously dynamic, but any part of your system can be similarly instrumented to expose their state in a running application.

You may also be interested in:

Comments